George Burroughs | |

|---|---|

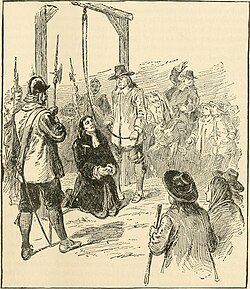

Execution of Reverend George Burroughs, 1901 drawing | |

| Born | c. 1652 |

| Died | August 19, 1692 (aged 39–40) |

| Alma mater | Harvard College |

| Occupation | Minister |

| Criminal charge(s) | Witchcraft (rehabilitated), Conspiracy with the Devil (rehabilitated) |

| Criminal penalty | Execution by hanging |

| Criminal status | Vacated |

| Parent(s) | Nathaniel Burroughs Rebecca Stiles Burroughs |

George Burroughs (c. 1652 – August 19, 1692) was a non-ordained Puritan preacher who was the only minister executed for witchcraft during the course of the Salem witch trials. He is remembered for reciting the Lord's Prayer flawlessly moments before his execution, something it was believed a witch could never do.

Early life and ministries

[edit]

George Burroughs was born in Suffolk, England in 1652,[1] although one source lists his birthplace as Virginia,[2] while another claims he was born in Scituate in 1650.[3]

He was raised by his mother in the town of Roxbury, Massachusetts.[4] In 1670, he completed his ministerial studies at Harvard College. In 1673, he married his first wife, Hannah Fisher; they had four children, three of whom survived.[5]

Burroughs was described by author Frances Hill as "confident, strong-willed, and decisive, a man of action as well as a preacher, unusually athletic and clever enough to do well in Harvard. Short of stature, muscular, dark-complexioned, he was highly attractive to women, as is shown by his winning the hand of a rich widow as his second wife when he was a mere village minister."[6]

In 1674, Burroughs served as pastor in the congregational church in Falmouth, Maine, until the town was destroyed by a Wabanaki raid in 1676.[4][7] He and his family fled to Massachusetts and, after a series of moves, he became the minister of Salem Village (now Danvers) in 1680 (where he would eventually be convicted of witchcraft and hanged). But he grew disillusioned with the community when they failed to pay his wages. When his wife Hannah died in childbirth in 1681, he resorted to borrowing money from community member John Putnam in order to cover her funeral expenses.[5] Burroughs was unable to repay the debt, and resigned from his post, leaving Salem in 1683.[8]

He obtained a ministry near Casco Bay in Maine, where he lived until 1688 when it too was subject to Indian attacks.[4][9] He next moved to Wells, Maine, believing it would be safer.[5] His second wife died in 1689, but he soon remarried to a woman named Mary, with whom he had a daughter.[7][10]

Accusation and trial for witchcraft

[edit]On April 30, 1692, Thomas Putnam and Jonathan Walcott submitted a complaint against Burroughs "for sundry acts of witchcraft".[11][12] The minister was arrested in Wells and brought to Salem Village on May 4.

Among Burroughs' accusers were personal enemies from his former congregation who had sued him for debt.[9] At his trial later in May, the evidence presented against him included his extraordinary feats of strength, such as lifting a musket by inserting his finger into the barrel (such feats of strength were presumed impossible without diabolical assistance).[13] His failure to attend communion was also cited as proof of guilt.[14] Moreover, he was suspected of killing his first two wives by witchcraft, and although clearly witchcraft was not involved, there is some historical evidence that he treated them poorly.[15] During the trial, Cotton Mather, a minister from Boston, said that Burroughs "had been famous for the barbarous use of his two late wives, all the country over"; and a girl accuser described a nightmarish vision she had in which "she stared into the blood-red faces of his dead wives."[16]

Suspicion of being a secret Baptist

[edit]Burroughs was also suspected of being a crypto-Baptist because he failed to baptize his younger children.[17] He admitted during cross-examination that on multiple occasions he had failed to take the sacrament at Sabbath services, and that only his eldest child was baptized.[12] These acts of religious non-conformity may have contributed to the hostility expressed towards him by Mather and other Congregational Church leaders.[18]

Execution and aftermath

[edit]Although the jury had discovered no witches' marks on his body, George Burroughs was nonetheless found guilty of witchcraft, and of conspiring with the Devil.[16] Before a record number of spectators, he was hanged on Proctor's Ledge at Gallows Hill in Salem on August 19, 1692.[5] He was the only minister to suffer this fate during New England's witchcraft hysteria.[9]

While standing on a ladder before the crowd, waiting to be hanged, Burroughs movingly recited the Lord's Prayer without making a single mistake, something generally considered by the Court of Oyer and Terminer to be impossible for a witch to do.[16] This feat stirred misgivings among the spectators. After the hanging, Cotton Mather from atop his horse sought to smother any sparks of discontent by reminding everyone that Burroughs had never been ordained,[16] and that he was convicted in a court of law. Mather spoke convincingly enough that four more executions took place.

Below is the original account of the hanging as compiled and published in 1700 by Robert Calef in More Wonders of The Invisible World, and later reprinted or relied upon by others including Charles Wentworth Upham and George Lincoln Burr:

Mr. Burroughs was carried in a cart with others, through the streets of Salem, to execution. When he was upon the ladder, he made a speech for the clearing of his innocency, with such solemn and serious expressions as were to the admiration of all present; his prayer (which he concluded by repeating the Lord's Prayer) was so well worded, and uttered with such composedness as such fervency of spirit, as was very Affecting, and drew tears from many, so that it seemed to some that the spectators would hinder the execution. The accusers said the black man [Devil] stood and dictated to him. As soon as he was turned off [hanged], Mr. Cotton Mather, being mounted upon a horse, addressed himself to the people, partly to declare that he [Mr. Burroughs] was no ordained Minister, partly to possess the people of his guilt, saying that the devil often had been transformed into the Angel of Light. And this did somewhat appease the people, and the executions went on; when he [Mr. Burroughs] was cut down, he was dragged by a Halter to a hole, or grave, between the rocks, about two feet deep; his shirt and breeches being pulled off, and an old pair of trousers of one executed put on his lower parts: he was so put in, together with Willard and Carrier, that one of his hands, and his chin, and a foot of one of them, was left uncovered.[19]

Later, the government of the Massachusetts colony recognized Burroughs' innocence and awarded 50 pounds damages to his widow and children, though this led to disputes over the division of the award among his heirs.[20] The musket reportedly used for demonstration purposes at the trial was for a time located at Fryeburg Academy in Fryeburg, Maine, having been taken there in 1808 for display in the Academy museum; but it was said to have been destroyed in the Academy fire of 1850.[21]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Brooks, Rebecca Beatrice (April 9, 2017). "The Witchcraft Trial of Reverend George Burroughs". History of Massachusetts Blog.

- ^ Wilcox, Clifton (2012). Witch-Hunt: The Assignment Of Blame. p. 27.

- ^ Genealogy of the Burroughs Family, 1894. Compiled by L.A. Burroughs, p. 4

- ^ a b c Hill 1997, p. 219.

- ^ a b c d "Foundation of Salem Village Parsonage". Salem Witch Museum. December 17, 2020.

- ^ Hill 1997, p. 55.

- ^ a b "George Burroughs: The Salem Minister and His Tragic Fate". 1692 Before and After. March 4, 2024.

- ^ Wilcox 2012, pp. 28–29.

- ^ a b c Karson, Anastasia (1998). "Revenge in the Salem Witchcraft Hysteria: The Putnam Family and George Burroughs" (PDF). Loyola University New Orleans.

- ^ Baxter, James Phinney, ed. (1889). The Baxter Manuscripts: Collections of the Maine Historical Society. Vol. 5. pp. 316–317. LCCN 06007664. OCLC 3505773 – via Library of Congress. An extant letter dated September 28, 1691, written by "Rev. Geo. Burrough" and co-signed by six Wells residents, asks the Maine Governor and Council to leave soldiers stationed in the town as protection against the threat of "heathens".

- ^ Boyer, Paul; Nissenbaum, Stephen, eds. (1993). "Complaint Against George Burroughs". Salem-Village Witchcraft: A Documentary Record of Local Conflict in Colonial New England. Northeastern University Press. p. 72. ISBN 978-1555531645.

- ^ a b "SWP No. 022: George Burroughs Executed, August 19, 1692". Salem Witch Trials – Documentary Archive and Transcription Project. Retrieved August 19, 2025 – via Scholars' Lab of the University of Virginia Library.

- ^ Godbeer, Richard (2018). The Salem Witch Hunt (2nd ed.). Boston, MA: Bedford/St. Martins. p. 140.

- ^ Holmes, Clive (2016). "The Opinion of the Cambridge Association, 1 August 1692: A Neglected Text of the Salem Witch Trials". New England Quarterly: A Historical Review of New England Life and Letters. 89 (4): 652. doi:10.1162/TNEQ_a_00567. S2CID 57558631.

- ^ Norton, Mary Beth (2003). In the Devil's Snare: The Salem Witchcraft Crisis of 1692. New York: Vintage eBooks. p. 125. ISBN 978-0-307-42636-9. OCLC 680524334.

- ^ a b c d Schiff, Stacy (August 31, 2015). "The Witches of Salem". The New Yorker.

- ^ "Baptists' Two Ordinances: Baptism and the Lord's Supper". baptistdistinctives.org. Baptist Distinctives. February 9, 2012. Retrieved July 31, 2023. Baptists do not believe that one must take the sacrament (or "ordinance") to be saved.

- ^ Baker, Emerson W. (August 19, 2014). "George Burroughs: Salem's perfect witch". oup.com. Oxford University Press. Retrieved July 31, 2023.

- ^ Calef, Robert (1823) [1700]. More Wonders of the Invisible World or The Wonders of the Invisible World Displayed. In Five Parts. Salem, Reprinted by John D. and T. C. Cushing, Jr. for Cushing and Appleton. pp. 212–213 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ "Reverend George Burroughs: Ringleader of the Salem Witches?". History of Massachusetts. April 9, 2017. Retrieved July 9, 2018.

- ^ Souther, Samuel (1864). The Centennial Celebration of the Settlement of Fryeburg. Tyler & Seagrave. Retrieved February 5, 2019.

Sources

[edit]- Hill, Frances (1997) [1995]. A Delusion of Satan: The Full Story of the Salem Witch Trials. New York: Da Capo Press. ISBN 0306807971. LCCN 97006817.

Further reading

[edit]- Upham, Charles (1980). Salem Witchcraft. New York: Frederick Ungar Publishing Co., 2 vv., v. 1 pp. 255, 278, 280, v. 2 pp. 140–63, 296–304, 319, 480, 482, 514.