List of colonial forces in the Eureka Rebellion

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Eureka Rebellion |

|---|

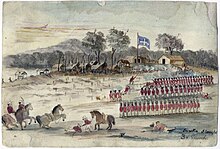

Eureka Stockade Riot by John Black Henderson (1854) |

| Origins

|

| The Eureka Rebellion

|

| High Treason trials

|

Australia portal Australia portal |

|

This is a list of British colonial forces of Australia that took part in the Battle of the Eureka Stockade in 1854 at Ballarat, Victoria, Australia. It was the culmination of the 1851–1854 Eureka Rebellion during the Victorian gold rush. The fighting resulted in at least 27 deaths and many injuries, the majority of casualties being rebels. The miners had various grievances, chiefly the cost of mining permits and the officious way the system was enforced. There was an armed uprising in Ballarat where tensions were brought to a head following the death of miner James Scobie. On 29 November 1854, the Eureka Flag was raised during a paramilitary display on Bakery Hill that resulted in the formation of rebel companies and the construction of a crude battlement on the Eureka lead.

Fortification of the Eureka lead

Following the oath swearing and Eureka Flag raising ceremony on Bakery Hill, about 1,000 rebels marched in double file to the Eureka lead, where the Eureka Stockade was constructed over the next few days. [1][2] It consisted of pit props held together as spikes by rope and overturned horse carts. Raffaello Carboni described it in his 1855 memoirs as being "higgledy piggledy".[3] It encompassed an area said to be one acre; however, that is difficult to reconcile with other estimates that have the dimensions of the stockade as being around 100 feet (30 m) x 200 feet (61 m).[4] Contemporaneous representations vary and render the stockade as either rectangular or semi-circular.[5] Testimony was heard at the high treason trials for the Eureka rebels that the stockade was four to seven feet high in places and was unable to be negotiated on horseback without being reduced.[6][note 1]

Lieutenant governor Charles Hotham feared that the goldfield's terrain would greatly favour the rebel snipers. Ballarat gold commissioner Robert Rede would instead order an early morning surprise attack on the rebel camp.[9] Carboni details the rebel dispositions along:

The shepherds' holes inside the lower part of the stockade had been turned into rifle-pits, and were now occupied by Californians of the I.C. Rangers' Brigade, some twenty or thirty in all, who had kept watch at the 'outposts' during the night.[10]

The location of the stockade has been described by Eureka veteran John Lynch as "appalling from a defensive point of view" as it was situated on "a gentle slope, which exposed a sizeable portion of its interior to fire from nearby high ground".[11][note 2]

In the early hours of 1 December 1854, the rebels were observed to be massing on Bakery Hill, but a government raiding party found the area vacated. The riot act was read to a mob that had gathered around Bath's Hotel, with mounted police breaking up the unlawful assembly. A three-man miner's delegation met with Rede to present a peace proposal; however, Rede was suspicious of the chartist undercurrent of the anti-mining tax movement and rejected the proposals as being the way forward.[15]

The rebels sent out scouts and established picket lines in order to have advance warning of Rede's movements and a request for reinforcements to the other mining settlements.[16] The "moral force" faction had withdrawn from the protest movement as the men of violence moved into the ascendancy. The rebels continued to fortify their position as 300-400 men arrived from Creswick's Creek, and Carboni recalls they were: "dirty and ragged, and proved the greatest nuisance. One of them, Michael Tuohy, behaved valiantly".[17] Once foraging parties were organised, there was a rebel garrison of around 200 men. Amid the Saturday night revelry, low munitions, and major desertions, Lalor ordered that any man attempting to leave the stockade be shot.[18]

Battle of the Eureka Stockade

Ballarat gold commissioner Robert Rede planned to send the combined military police formation of 276 men under the command of Captain John Thomas to attack the Eureka Stockade when the rebel garrison was observed to be at a low watermark. The police and military had the element of surprise timing their assault on the stockade for dawn on Sunday, the Christian Sabbath day of rest. The soldiers and police marched off in silence at around 3:30 am Sunday morning after the troopers had drunk the traditional tot of rum.[19] The British commander used bugle calls to coordinate his forces. The 40th regiment was to provide covering fire from one end, with mounted police covering the flanks. Enemy contact began at approximately 150 yards as the two columns of regular infantry and the contingent of foot police moved into position.[20]

According to military historian Gregory Blake, the fighting in Ballarat on 3 December 1854 was not one-sided and full of indiscriminate murder by the colonial forces. In his memoirs, one of Lalor's captains, John Lynch, mentions "some sharp shooting".[21] For at least 10 minutes, the rebels offered stiff resistance, with ranged fire coming from the Eureka Stockade garrison such that Thomas's best formation, the 40th regiment, wavered and had to be rallied. Blake says this is "stark evidence of the effectiveness of the defender's fire".[22]

The rebels eventually ran short of ammunition, and the government forces resumed their advance. The Victorian police contingent led the way over the top as the forlorn hope in a bayonet charge.[20][23] Carboni says it was the pikemen who stood their ground that suffered the heaviest casualties,[23] with Lalor ordering the musketeers to take refuge in the mine holes and crying out, "Pikemen, advance! Now for God's sake do your duty".[24] There were twenty to thirty Californians at the stockade during the battle. After the rebel garrison had already begun to flee and all hope was lost, a number of them gamely joined in the final melee bearing their trademark Colt revolvers.[25]

The strength of the various units in the government camp was: 40th regiment (infantry): 87 men; 40th regiment (mounted): 30 men; 12th regiment (infantry): 65 men; mounted police: 70 men; and the foot police: 24 men.[26] By the beginning of December, the police contingent at Ballarat had been surpassed by the number of soldiers from the 12th and 40th regiments.[20][27]

Key to military rank abbreviations

- LTC = Lieutenant-Colonel

- MAJ = Major

- CPT = Captain

- LT = Lieutenant

- ASST ENG = Assistant engineer

- DR = Doctor

- ASST SUR = Assistant surgeon

- ESN = Ensign

- SGT = Sergeant

- PVT = Private

12th regiment

The 12th (East Suffolk) Regiment of Foot traces its lineage back to the Duke of Norfolk's Regiment of Foot in 1685. In 1686, in became the Earl of Lichfield's Regiment of Foot. There was a reorganisation in 1751 following the War of the Austrian Succession, where it became the 12th Foot. The regiment took part in the Battle of Minden, where an allied army of British, Hanoverian, Hessian, and Prussians under Duke Ferdinand of Brunswick defeated the French commander Marshal Contades. This engagement took place in what became known as the "year of victories" and is commemorated in the regiment's battle honour. The regimental arms commemorate the defence of Gibraltar in 1779-1783. In 1782, it became the 12th (East Suffolk) Regiment. During the British conquest of Mysore in southern India were in action at the Battle of Seringapatam. Shortly before the Eureka Rebellion, the regiment was deployed to South Africa in the Kaffir War of 1851-1852. Other units within the regiment had served in Ireland. [28]

During the Eureka Rebellion, there was a skirmish involving the 12th Regiment and a mob of rebellious miners. Foot police reinforcements had already reached the Ballarat government outpost on 19 October 1854. A further detachment of the 40th (2nd Somersetshire) Regiment of Foot arrived a few days behind. On 28 November, the 12th Regiment arrived to reinforce the local government camp. As they moved near where the rebels ultimately made their last stand, there was a clash, where a drummer boy, John Egan and several other members of the convoy were attacked by a mob looking to loot the wagons.[29]

Tradition variously had it that Egan either was killed there and then or was the first casualty of the fighting on the day of the battle. However, his grave in Old Ballarat Cemetery was removed in 2001 after research carried out by Dorothy Wickham showed that Egan had survived and died in Sydney in 1860.[30]

After Eureka, the 12th were sent to New Zealand during the Second Maori War. In 1881, it became known as The Suffolk Regiment. There were postings throughout the British Empire, including in the First World War on the Western Front, Macedonia, and at Gallipoli and in Palestine. In the Second World War, the regiment took part in the 1940 Battle for France and served in Malaya and Singapore from 1941 to 1942. In the Burma campaign, it was in action at the Battle of Imphal. The regiment was amalgamated with The Royal Norfolk Regiment to form The East Anglican Regiment (Royal Norfolk and Suffolk) in 1959. In 1964, it became the 1st (Royal Norfolk and Suffolk) Battalion, The Royal Anglican Regiment, and then four years later the 1st Battalion. Records related to the regiment during the Eureka Rebellion are held at the Suffolk Record Office.[28]

| Name | Rank | Birth year | Birthplace | Status | Legacy and notes | Ref(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Robert Samuel Adair | PVT (no 3329) | unknown | unknown | wounded | Was shot through the hand in the battle. Listed as "severely wounded" in the report of Colonel Edward Macarthur published in the Sydney Morning Herald, 19 December 1854 edition. | [31][32] |

| B.T. Adams | ||||||

| William Adams | ||||||

| William Alderton | SGT (no 2929) | [33] | ||||

| Edward Archer | PVT (no 3090) | [33] | ||||

| George Banks Floyer Arden | Assistant surgeon | [33] | ||||

| Arthur Atkinson | CPT | [33] | ||||

| William Attwell | PVT (no 3248) | [33] | ||||

| Frederick Austin | ||||||

| Joseph Barden | PVT (no 2997) | [33] | ||||

| John Barrow | ||||||

| James Berry | ||||||

| John Birch | ||||||

| John Hill Birch | ||||||

| William Bird | PVT (no 3261) | [33] | ||||

| James Bourne | PVT (3087) | [33] | ||||

| Felix Boyle | PVT (no 3280) | [33] | ||||

| John Bozen | PVT (no 3210) | [33] | ||||

| Bradley Bartholomew | PVT (no 3034) | [33] | ||||

| William Bragg | PVT (1010) | [33] | ||||

| Benjamin Brooker | PVT (no 2924) | [33] | ||||

| George Brown | PVT (no 3157) | [33] | ||||

| James Brown | PVT (no 3304) | [33] | ||||

| John Bryan | PVT (no 2853) | [33] | ||||

| George Bryant | PVT (no 3291) | [33] | ||||

| William Butwell | ||||||

| Charles Campbell | ||||||

| Samuel Carter | ||||||

| Andrew Canty | ||||||

| Timothy Canty | ||||||

| Joseph Carrigan | ||||||

| Samuel Carter | ||||||

| John Casserly | ||||||

| Charles Chamberlain | ||||||

| Jonas Collins | ||||||

| Thomas Cole | ||||||

| William Colvin | ||||||

| Richard Coombs | ||||||

| Robert Cornish | ||||||

| John Cresswell | ||||||

| John Cridge | ||||||

| Haymen Crude | ||||||

| Thomas Culpeck | ||||||

| Martin Daley | ||||||

| William Davidson | ||||||

| Samuel Davis | ||||||

| Thomas Dawson | ||||||

| Thomas Denny | ||||||

| John Donegany | ||||||

| John Donohue | ||||||

| John Donolly | ||||||

| James Dow | ||||||

| John Doward | ||||||

| Peter Dowd | ||||||

| Thomas Downs | ||||||

| John Drury | ||||||

| John Duke | ||||||

| Frederick Dutton | ||||||

| William Earl | ||||||

| John Egan | ||||||

| Adam Ferguson | ||||||

| John Finn | ||||||

| Patrick Flynn | ||||||

| Daniel Flynn | ||||||

| William Earl | ||||||

| Joseph Forsyth | ||||||

| William French | ||||||

| George Fuller | ||||||

| Timothy Galvin | ||||||

| Alfred Geates | ||||||

| Henry Goddard | ||||||

| Edmund Grace | ||||||

| Robert Grant | ||||||

| Robert Griffin | ||||||

| Bryan Grimstone | ||||||

| William Grimwood | ||||||

| William Haddon | ||||||

| John Hall | [33] | |||||

| Henry Hall | ||||||

| William Hall | ||||||

| George Harding | ||||||

| John Hare | ||||||

| Richard Hargreaves | ||||||

| David Hawthorne | ||||||

| George Hayman | ||||||

| John Hearn | ||||||

| Thomas Hogan | ||||||

| Patrick Hynott | ||||||

| John Hurstwaite | ||||||

| Thomas Husband | ||||||

| James Huxley | ||||||

| William Hustable | ||||||

| Finniess Ing | ||||||

| James Jeffrey | ||||||

| William Jewell | ||||||

| William Johnstone | ||||||

| Robert Jones | ||||||

| Francis Keefe | ||||||

| Thomas Keen | ||||||

| John Kempt | ||||||

| John Knights | ||||||

| John Lackey | ||||||

| William Lang | ||||||

| William Lawrence | ||||||

| John Leekey | ||||||

| James Leonard | ||||||

| George Richard Littlehales | LT | [33] | ||||

| William Lumber | ||||||

| Joseph Lyness | ||||||

| John Marskand | ||||||

| George Littlehales | ||||||

| George Littlehales | ||||||

| William Martin | ||||||

| John McArdie | ||||||

| John McArthur | ||||||

| Edward McCormish | ||||||

| Thomas McDermott | ||||||

| John McGarry | ||||||

| Peter McGorrigle | ||||||

| Patrick McGrath | ||||||

| Edmund Medgley | ||||||

| John Melton | ||||||

| Jacob Moore | ||||||

| Michael Moran | ||||||

| Alfred Murray | ||||||

| Jeremiah Newell | ||||||

| Richard Norgrove | ||||||

| James Nowlan | ||||||

| Patrick O'Donnell | ||||||

| John Reynolds Palmer | ||||||

| Samuel Parker | ||||||

| John Parkhouse | ||||||

| James Parry | ||||||

| William Paul | ||||||

| Henry Perry | ||||||

| Henry Payne Rogers | ||||||

| William Percy | ||||||

| Michael Pinder | ||||||

| Simon Pritzler | ||||||

| William Queade | ||||||

| William Quinn | ||||||

| John Reed | ||||||

| Robert Reid | ||||||

| James Reilly | ||||||

| Samuel Reynolds | ||||||

| William Revel | ||||||

| John Sargeant | ||||||

| Garret Shanahan | ||||||

| James Sharkey | ||||||

| Edward Sharpe | ||||||

| George Sharpe | ||||||

| John Shovlin | ||||||

| John Smith | ||||||

| Thomas Smith | ||||||

| Jesse Spalding | ||||||

| James Stowe | ||||||

| John Sullivan | ||||||

| William Sutcliffe | ||||||

| George Swatman | ||||||

| John Thomas | ||||||

| Henry Thompson | ||||||

| John Thompson | ||||||

| Henry Timmons | ||||||

| William Turner | ||||||

| Daniel Vaughan | ||||||

| William Underwood | ||||||

| James Wagstaff | ||||||

| Andrew Walker | ||||||

| George Warner | ||||||

| John Waters | ||||||

| Robert Watson | ||||||

| William Webb | ||||||

| George Wend | ||||||

| William Wilkinson | ||||||

| H.L. Williams | ||||||

| ? Wise | ||||||

| George Wood | ||||||

| James Wright | ||||||

| Charles Yalden | ||||||

| Richard Young | [34][35] |

40th regiment

The 40th regiment traces its lineage back to 1717 at which time it was the Phillip's Regiment of Foot. It became the 40th Foot in 1782, and then in 1751, it was renamed the 40th (2nd Somersetshire) Foot. Its first battle honour was the capture along with other units of Montevideo, now the capital of Uraguay. During the war in Peninsular War, the regiment saw action at Roleia, Vimera, Talavera, Badajoz, Salamanca, and Vittoria. During the invasion of Napoleonic France, further honours were won at the Pyrenees, Nivelle, Orthes, and Toulouse. Later, the regiment saw action at the Battle of Waterloo. During the First Afghan War, the regiment was at Candahar, Ghuznee, and Cabool in 1842, and then at Maharajapore, India.[36]

The 40th regiment arrived in Victoria from England in October 1852 at the request of Lieutenant Governor Charles LaTrobe.

After the Eureka Rebellion, some members of the 40th regiment were posted to New Zealand. In 1881, it was amalgamated with the 82nd (The Prince of Wales's Volunteers) to form The South Lancashire Regiment (The Prince of Wales's Volunteers). During the First World War, the regiment saw action on the Western Front and in Gallipoli and Mesopotamia before being posted to Afghanistan in 1919. During the Second World War, it took part in the Battle of France in 1940. The regiment was then sent to the Far East for the Burma campaign and then participated in the Normandy D-Day landings in 1944. In 1958, it combined with The East Lancashire Regiment to form The Lancashire Regiment (The Prince of Wales's Volunteers). It amalgamated with The Loyal Regiment to become The Queen's Lancashire Regiment in 1970.[36]

| Name | Rank | Birth year | Birthplace | Status | Legacy and notes | Ref(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ? Adams | LT | [37] | ||||

| Thomas Bass | [37] | |||||

| Josiah Bigsby | PVT (no 3066) | [37] | ||||

| Thomas Bodely | [37] | |||||

| George Bowdler | LT | [37] | ||||

| Thomas Breadley | PVT (no 2026) | [37] | ||||

| Denis Brien | PVT (no 2816) | [37] | ||||

| Patrick Butler | [37] | |||||

| John Broadhurst | LT | [37] | ||||

| James Brown | [37] | |||||

| Thomas Bruce-Gardyne | LT | [37] | ||||

| John Bryan | [37] | |||||

| George Byford | PVT (no 3156) | [37] | ||||

| Patrick Burke | [37] | |||||

| Patrick Butler | [37] | |||||

| George Byford | [37] | |||||

| John Byrne | PVT (no ?) | [37] | ||||

| John Cameron | PVT (no ?) | [37] | ||||

| John Campbell | PVT (no ?) | [37] | ||||

| Samuel Clampet | PVT (no ?) | [37] | ||||

| William Cliff | PVT (no ?) | [37] | ||||

| Edwin Coles | PVT (no ?) | [37] | ||||

| Henry Collins | PVT (no ?) | [37] | ||||

| William Cork | PVT (no ?) | [37] | ||||

| Henry Cottes | PVT (no ?) | [37] | ||||

| John J. Crow | PVT (no ?) | [37] | ||||

| Martin Cusack | PVT (no ?) | [37] | ||||

| George Davis | ||||||

| Patrick Dwyer | ||||||

| Henry Fisher | ||||||

| Thomas Fitzgerald | ||||||

| William French | ||||||

| Thomas Frost | ||||||

| William Gardener | ||||||

| Thomas Gardyne | ||||||

| Michael Gay | ||||||

| James Glancy | ||||||

| James Gore | ||||||

| Daniel Hagerty | ||||||

| Israel Hales | ||||||

| Charles Hall | ||||||

| Edward Harris | ||||||

| James Harris | ||||||

| John Harvey | ||||||

| Daniel Hegarty | ||||||

| James Hill | ||||||

| George Howdler | ||||||

| Alfred Hurlestone | ||||||

| R.C Hutchings | ||||||

| Joseph Jubb | ||||||

| William Juniper | ||||||

| Joseph Keeble | ||||||

| James Kelly | ||||||

| Lawrence Kelly | ||||||

| Hugh King | ||||||

| Johm Knowles | ||||||

| Charles Ladbrook | ||||||

| Francis Langham | ||||||

| Frederick Langham | ||||||

| John Langham | ||||||

| James Louge | ||||||

| Patrick Lynot? | ||||||

| William MacCarron | ||||||

| John Mallagh | ||||||

| William Manella | ||||||

| John Manning | PVT | |||||

| Michael McAdam | ||||||

| Peter McCabe | ||||||

| Justin MacCarthy | ||||||

| John McEvoy | ||||||

| Henry McDermott | ||||||

| Thomas McDermott | ||||||

| John McGurk | ||||||

| Samuel McKee | ||||||

| John Macoboy | ||||||

| William Manella | ||||||

| Michael McAdam? | ||||||

| Charles Meacham | ||||||

| Charles Miner | ||||||

| William Mole | ||||||

| Arthur Mollers | ||||||

| Michael Moran | ||||||

| Lot Mullen | ||||||

| Michael Murphy | ||||||

| William Murrell | ||||||

| Charles Must | ||||||

| John Neill | ||||||

| Thomas Nelson | ||||||

| Mark Noble | ||||||

| Michael O'Connel | ||||||

| Edward O'Dell | ||||||

| Bernard O'Donnell | ||||||

| Patrick O'Keefe | ||||||

| Henry Patchett | ||||||

| William Pearce | ||||||

| William Prayle | ||||||

| Joseph Rayner | ||||||

| Thomas Reed | ||||||

| Bailey Richards | ||||||

| Patrick Reilly | ||||||

| William Revel | ||||||

| Bailey Richards | ||||||

| Thomas Richards | ||||||

| William Richardson | ||||||

| Edward Riley | ||||||

| Michael Roney | ||||||

| John Ryan | ||||||

| John Sharland | ||||||

| Patrick Sinnott | ||||||

| William Smith | ||||||

| Cornelius Sorrell | ||||||

| James Stowe | ||||||

| Patrick Sullivan | ||||||

| William Swan | ||||||

| John Thomas | ||||||

| James Turner | ||||||

| Thomas Valiant | ||||||

| Joseph Wall | ||||||

| Patrick Walsh | ||||||

| William Webb | ||||||

| Cornelius Whelan | ||||||

| Henry Wise | ||||||

| Hans White | ||||||

| John White? | ||||||

| John Warren White | CPT (no 2958) | unknown | unknown | survivor | Warren was a captain with the 40th regiment who was at the Eureka Stockade. He was part of the military convoy that arrived in Ballarat on 28 November 1854. It is said that during the battle, White cornered a rebel miner within the stockade. | [38][39] |

Other British regulars

| Name | Rank | Birth year | Birthplace | Status | Legacy and notes | Ref(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Timothy Calvin | unknown (no 3208) | unknown | unknown | survivor | — | [40] |

| William Friend | unknown (no 2958) | unknown | unknown | survivor | — | [40] |

| James Hammond | unknown | unknown | unknown | died of wounds | Hammond may have been at the Eureka Stockade serving with the 40th regiment. He is not listed as having ever been posted to Ballarat. However, Hammond is mentioned as having died on the return trip to Melbourne after the battle. | [41] |

| Patrick Hynes | PVT | unknown | unknown | survivor | Hynes was a private who was at the Eureka Stockade. He was the first cousin of John and Thomas Hynes brothers, the former having died during the battle. There are records that after the colonial forces returned to the government camp and were confined, one of the soldiers, almost certainly Hynes, asked for leave to attend the funeral of a relative who was among the fallen miners. | [42] |

| ? Keene | unknown | unknown | unknown | survivor | — | [37] |

| George King | SGT | unknown | unknown | survivor | King was a sergeant with the foot police at the Eureka Stockade. He was involved in apprehending Jacob Sorenson, who was later among the thirteen rebel prisoners put on trial for high treason. | [43] |

| Patrick Shanahan | unknown | unknown | unknown | survivor | — | [37] |

Key to police rank abbreviations

- INS = Inspector

- SI = Sub-inspector

- SGT = Sergeant

- TRP = Trooper

- CON = Constable

Victorian police

Following the separation of Victoria from New South Wales on 1 July 1851, there was a need for the Victorian authorities to raise a police force. Initially, there were seven jurisdictions and departments: Melbourne and County of Bourke, the city of Geelong, the goldfields settlements, the marine police, the mounted police, and the regional bench constabulary. The Victorian police, as it is known today, was officially formed on 8th January 1853. In the 1850s, the police were an armed paramilitary gendarmerie where troopers and police were garrisoned at central locations, and there was no interaction with the civilian population. In Ballarat where there was a police camp at Golden later moved to Camp Street in mid 1852. Many serving police officers resigned and headed for the goldfields, with the Melbourne and County of Bourke commands falling from 139 men to 78.[44] To cope with the expansion of the mining industry, the Victorian government raised police wages 3d from 5/9 to 6/- per day and resorted to recruiting at least 130 former convicts from Tasmania who were prone to brutal means.[44] They would get a fifty per cent commission from all fines imposed on unlicensed miners and sly grog sellers. Plainclothes officers enforced prohibition, and those involved in the illegal sale of alcohol were initially handed 50-pound fines. There was no profit for police from subsequent offences, that were instead punishable by months of hard labour. This led to the corrupt practice of police demanding blackmail of 5 pounds from repeat offenders.[45][46][47] By January 1853, there were 230 mounted police throughout Victoria. By 1855, the number had risen to 485, including nine mounted detectives.[48] Most police officers lived in tents, and prior to the construction of a wooden lock-up, the prisoners would be chained to a large gum tree with an image being made by James Meek. When John Sadleir arrived on 6 January 1853, the tree had been cut down, and the prisoners were still chained to the tree where it fell.

There were no known casualties among the Victorian police contingent, who spearheaded the attack on the stockade. George Webster, the chief assistant civil commissary and magistrate, testified in the 1855 Victorian High Treason trials that upon entering the stockade, the besieging forces "immediately made towards the flag, and the police pulled down the flag".[49] John King testified, "I took their flag, the southern cross, down – the same flag as now produced."[50] In his report dated 14 December 1854, Captain John Thomas mentioned "the fact of the Flag belonging to the Insurgents (which had been nailed to the flagstaff) being captured by Constable King of the Force".[51] King had volunteered for the honour while the battle was still raging.[52] W. Bourke, a miner residing about 250 yards from the stockade, recalled that: "The police negotiated the wall of the Stockade on the south-west, and I then saw a policeman climb the flag pole. When up about 12 or 14 feet the pole broke, and he came down with a run".[53]

| Name | Rank | Birth year | Birthplace | Status | Legacy and notes | Ref(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thomas Atkins | CON | unknown | unknown | survivor | Atkins was with the foot police at the Eureka Stockade | [54][55] |

| John Badcock | TPR | unknown | unknown | survivor | Badcock was with the mounted police at the Eureka Stockade. Later gave evidence against James Beattie, Raffaello Carboni, and Phillips at the 1855 Victorian High Treason trials. | [56][57] |

| Wiliam Barry | CON | c.1833 | unknown | survivor | His obituaries published in the Hobart Mercury (5 May 1898) and the Goulburn Evening Penny Post (5 May 1898) mention that he was a police orderly at the Eureka Stockade. | [58] |

| Robert Calvin | SGT | unknown | unknown | survivor? | Calvin was a sergeant of police in 1854. May have been at the Eureka Stockade. | [59] |

| Charles Carter | SI | 1813 | unknown | survivor | Carter was a sub-inspector in the foot police at the Eureka Stockade | [60] |

| Hussey Chomley | SI | unknown | unknown | survivor | Chomley was a sub-inspector and second in command of a police detachment kept in reserve at the Eureka Stockade on 3 December 1854 | [61] |

| Thomas Conboy | TRP | unknown | unknown | survivor? | Conboy may have served with the mounted police at the Eureka Stockade | [62] |

| John Concritt | TRP | unknown | unknown | survivor | Concritt served with the mounted police at the Eureka Stockade. In February 1855, he testified at the trial of Raffaello Carboni. | [63] |

| Michael Costelloe | CON | unknown | unknown | survivor? | Costello was a constable at Ballarat during the rebellion. Along with William Scharlach and John Dougherty, he was present when James Bentley was first interviewed by the police. Costello also gave evidence at the subsequent inquest into the death of James Scobie. He was questioned about a private meeting between Bentley and magistrate John D'Ewes during the former's trial. | [64] |

| Thomas Crowther | SGT | unknown | unknown | survivor? | Crowther was a police sergeant who was present when the Eureka Hotel was burned. He testified that he saw Andrew McIntyre enter the bowling alley belonging to John Emery and tear down wallpaper that was used by the arsonists to kindle the fire. | [65] |

| John Culkin | TPR | unknown | unknown | survivor | Culkin served with the mounted police at the Eureka Stockade. During the battle, he struck John Phelan with the flat of his sword. | [66][67] |

| Henry Downing | TRP | unknown | Canada | survivor | His obituary published in the Melbourne Herald, 3 April 1917 edition, mentions that he was a Canadian who was with the mounted police at the Eureka Stockade. When in the reminiscent mood, he would relate his many stirring memories of the Stockade". He was the brother of Sir George Downing of the British Royal Navy. | [68] |

| Gordon Evans | INS | unknown | unknown | not present | Evans was an inspector of police at Ballarat during the Eureka Rebellion. He was present at the public meeting on 17 October 1854. When called as a witness to the board of inquiry into the burning of Bentley's Hotel, Evans felt that the riot act should have been read. However, he was also worried that using force might only worsen the situation by using force and lead to loss of life. He testified that Henry Westoby helped to set fire to the Eureka Hotel and then again at the 1855 Victorian high treason trials. | [69] |

| Robert Evans | INS | unknown | unknown | not present | Evans was appointed police inspector of Ballarat In February 1854. He was there to take the wounded Henry Powell's statement at the Albion Hotel after the battle. | [70] |

| Henry Foster | INS | unknown | unknown | survivor? | Foster was a police inspector in Ballarat. | [71] |

| Samuel Stackpole Furnell | SI | unknown | unknown | survivor | Furnell was a sub-inspector and served with the foot police at the Eureka Stockade on 3 December 1854. | [72] |

| George Fraser | CON | unknown | unknown | survivor | Fraser was with the foot police at the Eureka Stockade | [73] |

| Gartner ? | ||||||

| John Gillman | ||||||

| Joseph Glover | ||||||

| Henry Goodenough | ||||||

| William Graham | ||||||

| John Hagherty | ||||||

| Gerald Hamilton | ||||||

| Benjamin Hawkshaw | ||||||

| William Kelly | ||||||

| John King | ||||||

| Ladislaus Kossak | ||||||

| James Langley | ||||||

| Thomas Langley | ||||||

| Michael Lawler | ||||||

| James Lord | ||||||

| Robert McLister | ||||||

| Thomas Milne | ||||||

| Robert Milne | ||||||

| Henry Moore | ||||||

| William Nevil | ||||||

| William Nolan | ||||||

| Constable Nugent | ||||||

| Michael O'Brien | ||||||

| James Pepper | ||||||

| Andrew Peters | ||||||

| Edward Preece | ||||||

| Robert Pulley | ||||||

| Johnl Sadlier | ||||||

| William Scharlach | ||||||

| Peter Smith | ||||||

| Patrick Sullivan | ||||||

| William Thompson | ||||||

| Robert Tulley | ||||||

| Edward Viret | ||||||

| ? Wendon | ||||||

| William Scharlach | ||||||

| A. Warren White | ||||||

| Michael Wigley | ||||||

| Thomas Wood | ||||||

| Henry Wright | ||||||

| Maurice Ximenes[74] |

See also

Notes

- ^ Peter Lalor himself said the wooden structure was never meant to be a fortress, saying "it was nothing more than an enclosure to keep our own men together, and was never erected with an eye to military defence".[7] However Peter FitzSimons says that Lalor may have downplayed the fact that the Eureka Stockade may have been intended as something of a fortress, at a time when "it was very much in his interests" to do so.[8]

- ^ A detachment of 800 men, which included "two field pieces and two howitzers" under the commander in chief of the British forces in Australia, Major General Sir Robert Nickle, who had seen action during the 1798 Irish rebellion, arrived after the insurgency had been put down.[12][13] In 1860, Withers stated in a lecture that "The site was most injudicious for any purpose of defence as it was easily commanded from adjacent spots, and the ease with which the place could be taken was apparent to the most unprofessional eye".[14]

References

- ^ Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni 2004, p. xiii, 196.

- ^ Carboni 1855, p. 59.

- ^ Carboni 1855, pp. 77, 81.

- ^ FitzSimons 2012, p. 648, note 12.

- ^ Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni 2004, pp. 190–191.

- ^ The Queen v Joseph and others, 29 (Supreme Court of Victoria 1855).

- ^ Historical Studies: Eureka Supplement 1965, p. 37. sfn error: no target: CITEREFHistorical_Studies:_Eureka_Supplement1965 (help)

- ^ FitzSimons 2012, p. 648, footnote 13.

- ^ Three Despatches From Sir Charles Hotham 1978, p. 2. sfn error: no target: CITEREFThree_Despatches_From_Sir_Charles_Hotham1978 (help)

- ^ Carboni 1855, p. 96.

- ^ Blake 2012, p. 88.

- ^ Three Despatches From Sir Charles Hotham 1978, p. 7. sfn error: no target: CITEREFThree_Despatches_From_Sir_Charles_Hotham1978 (help)

- ^ Blake 1979, p. 93.

- ^ Harvey 1994, p. 24.

- ^ MacFarlane 1995.

- ^ Withers 1999, p. 94.

- ^ Carboni 1855, pp. 78–79.

- ^ Withers 1999, pp. 116–117.

- ^ "Eureka Stockade | Ergo". ergo.slv.vic.gov.au. Retrieved 2022-08-24.

- ^ a b c Thomas, John Wellesley (3 December 1854). Captain Thomas reports on the attack on the Eureka Stockade to the Major Adjutant General (Report). Public Record Office Victoria. Archived from the original on 4 April 2019. Retrieved 7 July 2024.

- ^ Lynch 1940, p. 30.

- ^ Blake 2012, p. 133.

- ^ a b Carboni 1855, p. 98.

- ^ Blake 1979, p. 81.

- ^ Blake 2012, pp. 136–138.

- ^ Withers 1999, p. 111.

- ^ "SERIOUS RIOT AT BALLAARAT". The Argus. No. 2357. Melbourne. 28 November 1854. p. 4. Retrieved 7 July 2024 – via National Library of Australia.

- ^ a b Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni 2004, pp. 74–75.

- ^ Clark 1987, p. 73.

- ^ Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni 2004, pp. 174–175.

- ^ Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni 2004, p. 3.

- ^ https://www.eurekapedia.org/Robert_Adair

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni 2004, p. 77.

- ^ Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni 2004, pp. 74–79.

- ^ https://www.eurekapedia.org/Military

- ^ a b Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni 2004, p. 75.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni 2004, p. 79.

- ^ Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni 2004, pp. 74–79, 538.

- ^ https://www.eurekapedia.org/Military

- ^ a b Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni{2004, p. 79. sfn error: no target: CITEREFCorfieldWickhamGervasoni{2004 (help)

- ^ Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni{2004, p. 24. sfn error: no target: CITEREFCorfieldWickhamGervasoni{2004 (help)

- ^ Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni{2004, p. 286. sfn error: no target: CITEREFCorfieldWickhamGervasoni{2004 (help)

- ^ Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni 2004, p. 306.

- ^ a b Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni 2004, p. 429.

- ^ Clark 1987, p. 67.

- ^ Barnard 1962, p. 260.

- ^ "Alcohol on the Goldfields". Sovereign Hill. 21 February 2014. Retrieved 18 June 2022.

- ^ https://eurekapedia.org/Police

- ^ The Queen v Joseph and others, 35 (Supreme Court of Victoria 1855).

- ^ "Continuation of the State Trials". The Sydney Morning Herald. Sydney. 5 March 1855. p. 3. Retrieved 17 November 2020 – via Trove.

- ^ Thomas, John Wellesley (14 December 1854). Capt. Thomas' report – Flag captured (Report). Colonial Secretary's Office. Archived from the original on 12 April 2019. Retrieved 7 December 2020 – via Public Record Office Victoria.

- ^ FitzSimons 2012, p. 477.

- ^ Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni 2004, pp. 66–67.

- ^ Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni 2004, p. 22.

- ^ "Thomas Atkins - eurekapedia". www.eurekapedia.org.

- ^ Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni 2004, p. 23.

- ^ "Thomas Atkins - eurekapedia". www.eurekapedia.org.

- ^ "William Barry - eurekapedia". www.eurekapedia.org.

- ^ "Robert Calvin - eurekapedia". www.eurekapedia.org.

- ^ Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni 2004, pp. 107–108.

- ^ Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni 2004, pp. 114–115.

- ^ "Thomas Conboy - eurekapedia". www.eurekapedia.org.

- ^ Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni 2004, p. 124.

- ^ Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni 2004, p. 127.

- ^ Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni 2004, p. 134.

- ^ Blake 2009, p. 37. sfn error: no target: CITEREFBlake2009 (help)

- ^ https://eurekapedia.org/John_Culkin

- ^ https://eurekapedia.org/Henry_Downing

- ^ Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni 2004, pp. 195–196.

- ^ https://eurekapedia.org/Robert_Evans

- ^ Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni 2004, p. 209.

- ^ Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni 2004, pp. 212–213.

- ^ https://eurekapedia.org/George_Fraser

- ^ https://eurekapedia.org/Police

Bibliography

- Barnard, Marjorie (1962). A History of Australia. Sydney: Angus and Robertson.

- Blake, Gregory (2012). Eureka Stockade: A ferocious and bloody battle. Newport: Big Sky Publishing. ISBN 978-1-92-213204-8.

- Blake, Les (1979). Peter Lalor: The Man from Eureka. Belmont, Victoria: Neptune Press. ISBN 978-0-90-913140-1.

- Carboni, Raffaello (1855). The Eureka Stockade: The Consequence of Some Pirates Wanting a Quarterdeck Rebellion. Melbourne: J. P. Atkinson and Co. – via Project Gutenberg.

- Clark, Manning (1987). A History of Australia. Vol. IV: The Earth Abideth Forever 1851-1888. Carlton: Melbourne University Press. ISBN 9780522841473.

- Corfield, Justin; Wickham, Dorothy; Gervasoni, Clare (2004). The Eureka Encyclopedia. Ballarat: Ballarat Heritage Services. ISBN 978-1-87-647861-2.

- FitzSimons, Peter (2012). Eureka: The Unfinished Revolution. Sydney: Random House Australia. ISBN 978-1-74-275525-0.

- Harvey, Jack (1994). Eureka Rediscovered: In search of the site of the historic stockade. Ballarat: University of Ballarat. ISBN 978-0-90-802664-7.

- Historical Studies: Eureka Supplement (2nd ed.). Melbourne: Melbourne University Press. 1965.

- Lynch, John (1940). Story of the Eureka Stockade: Epic Days of the Early Fifties at Ballarat (Reprint ed.). Melbourne: Australian Catholic Truth Society.

- MacFarlane, Ian (1995). Eureka from the Official Records. Melbourne: Public Record Office Victoria. ISBN 978-0-73-066011-8.

- Three Despatches From Sir Charles Hotham. Melbourne: Public Record Office. 1981.

- Withers, William (1999). History of Ballarat and Some Ballarat Reminiscences. Ballarat: Ballarat Heritage Service. ISBN 978-1-87-647878-0.

Further reading

- Eurekapedia

External links

- Ballarat and District Genealogical Society

- Ballarat Heritage Services

- Ballarat Historical Society

- Eureka Centre Ballarat

- Public Record Office Victoria

- Sovereign Hill/Gold Museum

- State Library of Victoria