The Mechanical Turk, also known as the Automaton Chess Player (German: Schachtürke, lit. 'chess Turk'; Hungarian: A Török), or simply The Turk, was a fraudulent chess-playing machine constructed in 1770, which appeared to be able to play a strong game of chess autonomously, but whose pieces were in reality moved via levers and magnets by a chess master hidden in the machine's lower cavity. The machine was toured and exhibited for 84 years as an automaton, and continued giving occasional exhibitions until 1854, when it was destroyed in a fire. In 1857, an article published by the owner's son revealed that it was an elaborate hoax; a fact suspected by some but never fully explained while the machine still existed.

Constructed and unveiled in 1770 by Wolfgang von Kempelen (1734–1804) to impress Empress Maria Theresa of Austria, the mechanism not only played well in games of chess but also could perform the knight's tour, a puzzle that requires the player to move a knight to visit every square of a chessboard exactly once.

The Turk was in fact a mechanical illusion that won most games, including those against statesmen such as Napoleon Bonaparte and Benjamin Franklin. The device was purchased in 1804 by Johann Nepomuk Mälzel, who continued to exhibit it. The chess masters who operated it over this later period included Johann Allgaier, Boncourt, Aaron Alexandre, William Lewis, Jacques Mouret and William Schlumberger, but its operators during Kempelen's original tour remain unknown.

Construction

[edit]

A performance by the French illusionist François Pelletier at the court of Maria Theresa of Austria in Schönbrunn Palace prompted Wolfgang von Kempelen to promise to soon return to the Palace with an invention that would surpass Pelletier's illusions.[2]

The result was the Automaton Chess-player,[4][5] later known as the Turk. The machine consisted of a life-sized model of a human head and torso, with a black beard and grey eyes,[6] and dressed in Ottoman robes and a turban – "the traditional costume", according to journalist and author Tom Standage, "of an oriental sorcerer". Its left arm held a long Ottoman smoking pipe when at rest, while its right lay on a cabinet[7] that was "three feet and a half long, two feet deep, and two and a half feet high".[8][a] Placed on the top of the cabinet was a chessboard, which measured 18 inches (460 mm) on each side. The front of the cabinet consisted of three doors, an opening and a drawer, which could be opened to reveal a red and white ivory chess set.[9]

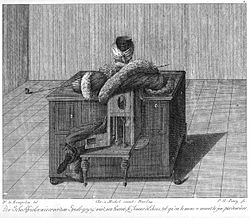

The interior of the machine had complications designed to mislead observers.[2] When opened on the left, the front doors of the cabinet exposed a number of gears and cogs resembling clockwork. The section was designed so that if the back doors of the cabinet were open at the same time one could see through the machine. The other side of the cabinet did not house machinery; instead it contained a red cushion and some removable parts, as well as brass structures. This too was designed to provide a clear line of vision through the machine. Underneath the robes of the Ottoman model, two other doors were hidden. These also exposed clockwork machinery and provided a similarly unobstructed view through the machine. The design allowed the presenter of the machine to open every available door to the public, to maintain the illusion.[10]

Neither the clockwork visible on the left side of the machine nor the drawer that housed the chess set extended fully to the rear of the cabinet; they instead went only one-third of the way. A sliding seat was also installed, allowing the operator inside to move from place to place and thus evade observation as the presenter opened various doors. The sliding of the seat caused dummy machinery to slide into its place to further conceal the person inside the cabinet.[11]

The chessboard on the top of the cabinet was thin enough to allow for a magnetic attraction. Each chess piece had a small, strong magnet attached to its base, and when placed on the board it would attract a magnet attached to a string under its place on the board. This allowed the operator inside the machine to see which pieces moved where on the chessboard.[12] The underside of the chessboard was marked with squares numbered 1–64, helping the operator to see which places on the board were affected by a player's move.[13] The internal magnets were positioned so that outside magnetic forces did not influence them, and Kempelen would often allow a large magnet to sit at the side of the board in an attempt to show that the machine was not influenced by magnetism.[14]

As a further means of misdirection, the Turk came with a small wooden coffin-like box that the presenter would place on the top of the cabinet.[2] While Johann Nepomuk Mälzel, a later owner of the machine, did not use the box,[15] Kempelen often peered into it during play, suggesting that it controlled some aspect of the machine. Some believed the box to have supernatural power; Karl Gottlieb von Windisch wrote in his 1784 book Inanimate Reason that "[o]ne old lady, in particular, who had not forgotten the tales she had been told in her youth . . . went and hid herself in a window seat, as distant as she could from the evil spirit, which she firmly believed possessed the machine."[16]

The interior also contained a pegboard chessboard connected by something like a pantograph to the model's left arm. The metal pointer on the pantograph moved over the interior chessboard and would simultaneously move the arm of the Turk over the chessboard on the cabinet. The range of motion allowed the operator to move the Turk's arm up and down, while turning the lever would open and close the Turk's hand, allowing it to grasp the pieces on the board. The board and mechanism were visible to the operator by candlelight.[17] Other parts of the machinery made a clockwork sound when the Turk made a move, further adding to the machinery illusion;[18] and the Turk could make various facial expressions.[19] A voice box was added following the Turk's acquisition by Mälzel, allowing the machine to say "Échec!" (French for "Check!") during games.[20]

An operator inside the machine had tools to assist in communicating with the presenter. Two brass discs equipped with numbers were positioned opposite each other on the inside and outside of the cabinet. A rod rotated the discs to a desired number, which acted as a code between the two.[21]

Exhibition

[edit]The Turk made its debut in 1770 at Schönbrunn Palace, about six months after Pelletier's act. Kempelen addressed the court, presenting what he had built, and began the demonstration of the machine and its parts. With every showing of the Turk, Kempelen began by opening the doors and drawers of the cabinet, allowing members of the audience to inspect the machine. Following this display, Kempelen would announce that the machine was ready for a challenger.[9]

Kempelen insisted that the Turk would use the white pieces and have the first move. (The convention that White moves first was not yet established, so there was no redundancy.) Between moves the Turk kept its left arm on the cushion. It could nod twice if it threatened its opponent's queen and three times upon placing the king in check. If an opponent made an illegal move the Turk would shake its head, move the piece back and make its own move, thus forcing a forfeit of its opponent's move.[22] Louis Dutens, a traveller who observed a showing of the Turk, attempted to trick the machine "by giving the Queen the move of a Knight, but my mechanic opponent was not to be so imposed upon; he took up my Queen and replaced her in the square from which I had moved her".[23] Kempelen made it a point to traverse the room during the match, and invited observers to bring magnets, irons and lodestones[vague] to the cabinet to test whether the machine was run by magnets or weights. The first person to play against the Turk was Count Ludwig von Cobenzl, an Austrian courtier at the palace. Along with other challengers that day, he was quickly defeated, with observers of the match stating that the machine played aggressively and typically beat its opponents within thirty minutes.[24]

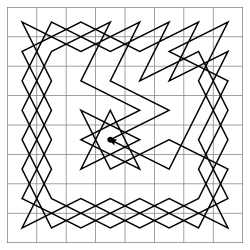

Another part of the machine's exhibition was the completion of the knight's tour, a famed chess puzzle, requiring the player to move a knight around a chessboard, visiting each square once along the way. While most experienced chess players of the time still struggled with this, the Turk was capable of completing the tour without any difficulty from any starting point thanks to a pegboard with a mapping of the puzzle laid out.[25]

The Turk could also converse with spectators using a letter board. The operator, whose identity during the period when Kempelen presented the machine at Schönbrunn Palace is unknown,[26] was able to do this in English, French and German. Carl Friedrich Hindenburg, a university mathematician, kept a record of the conversations during the Turk's time in Leipzig and published it in 1784 as Ueber den Schachspieler des Herrn von Kempelen: Nebst einer Abbildung und Beschreibung seiner Sprachmaschine.[27] Topics of questions put to and answered by the Turk included its age, marital status and secret workings.[28]

European tour

[edit]Following word of its debut, interest in the machine grew across Europe. Kempelen, however, avoided exhibiting the Turk, often lying about the machine's repair status to prospective challengers. Von Windisch wrote at one point that Kempelen "refused to gratify his friends, and many curious people of different countries, who wished to see this boasted machine, under a pretence that it had received damage by being removed from place to place".[29] In the decade following its debut at Schönbrunn Palace the Turk only played one opponent, Sir Robert Murray Keith, a Scottish noble, and Kempelen went as far as dismantling the Turk entirely following the match.[30] Kempelen was quoted as referring to the invention as a "mere bagatelle", as he was not pleased with its popularity and would rather continue work on steam engines and machines that replicated human speech.[31]

In 1781, Kempelen was ordered by Emperor Joseph II to reconstruct the Turk and deliver it to Vienna for a state visit from Grand Duke Paul of Russia and his wife. The appearance was so successful that the Grand Duke suggested a tour of Europe for the Turk, a request to which Kempelen reluctantly agreed.[32]

The Turk began its European tour in April 1783, in France. A stop at Versailles beginning on 17 April preceded an exhibition in Paris, where it lost a match to Charles Godefroy de La Tour d'Auvergne. Upon arrival in Paris in May, it was displayed to the public and played a variety of opponents, including a lawyer named Mr. Bernard who ranked second in chess ability.[33] Demands increased for a match with François-André Danican Philidor, considered the best chess player of his time.[34] Moving to the Café de la Régence, the machine played many of the most skilled players, often losing (e.g. against Bernard and Verdoni),[35] until securing a match with Philidor at the Académie des Sciences. While Philidor won his match with the Turk, Philidor's son noted that his father called it "his most fatiguing game of chess ever"[36] The Turk's final game in Paris was against Benjamin Franklin, then the American ambassador to France. Franklin reportedly enjoyed the game with the Turk and was interested in the machine for the rest of his life, keeping a copy of Philip Thicknesse's book The Speaking Figure and the Automaton Chess Player, Exposed and Detected in his personal library.[37]

Following his tour of Paris, Kempelen moved the Turk to London, where it was exhibited daily for five shillings. Thicknesse was a skeptic and sought out the Turk in an attempt to expose its inner workings.[38] While he respected Kempelen as "a very ingenious man",[2] he asserted that the Turk was an elaborate hoax with a small child inside the machine, describing the machine as "a complicated piece of clockwork . . . which is nothing more, than one, of many other ingenious devices, to misguide and delude the observers".[39]

After a year in London, Kempelen and the Turk travelled to Leipzig, stopping in various European cities along the way. From Leipzig, it went to Dresden, where Joseph Friedrich Freiherr von Racknitz viewed it and published his findings in Ueber den Schachspieler des Herrn von Kempelen und dessen Nachbildung, along with illustrations showing how he believed the machine operated.[40] It then moved to Amsterdam, after which Kempelen is said to have accepted an invitation to the Sanssouci palace in Potsdam. Frederick is said to have enjoyed the Turk so much that he paid a large sum to Kempelen in exchange for its secrets. Frederick never divulged these but was reportedly disappointed to learn how the machine worked.[41] However, this story is apocryphal: there is no evidence of the Turk's encounter with Frederick, the first mention of which comes in the early 19th century, by which time the Turk was incorrectly said to have played against George III of Great Britain.[42] It seems most likely that the machine stayed dormant at Schönbrunn Palace for over two decades, although Kempelen attempted unsuccessfully to sell it in the final years before his death at 70 on 26 March 1804.[43]

Mälzel

[edit]Following the death of Kempelen, the Turk remained unexhibited until 1805, when Kempelen's son decided to sell it to Johann Nepomuk Mälzel, a Bavarian musician with an interest in machines and devices. Mälzel, whose successes included patenting a form of metronome, had tried to buy the Turk before Kempelen's death. That attempt failed, owing to Kempelen's asking price of 20,000 francs; his son sold the machine to Mälzel for half this sum.[44] On acquiring the Turk, Mälzel learned how it worked and made repairs to return it to working order. His goal was to make explaining the Turk a greater challenge. While the completion of this goal took ten years, the Turk still made appearances, most notably with Napoleon Bonaparte.[45]

In 1809, Napoleon I of France arrived at Schönbrunn Palace to play the Turk. According to an eyewitness report, Mälzel took responsibility for the construction of the machine while preparing the game, and the Turk (Johann Baptist Allgaier) saluted Napoleon before the start of the match. The details of the match have been published over the years in numerous accounts, many of them contradictory.[46] According to Bradley Ewart, it is believed that the Turk sat at its cabinet, and Napoleon sat at a separate chess table. Napoleon's table was in a roped-off area and he was not allowed to cross into the Turk's area, with Mälzel crossing back and forth to make each player's move and allowing a clear view for the spectators. In a surprise move, Napoleon took the first turn instead of allowing the Turk to make the first move, as was usual; but Mälzel allowed the game to continue. Shortly thereafter, Napoleon attempted an illegal move. Upon noticing the move, the Turk returned the piece to its original spot and continued the game. Napoleon attempted the illegal move a second time, and the Turk responded by removing the piece from the board entirely and taking its turn. Napoleon then attempted the move a third time, the Turk responding with a sweep of its arm, knocking all the pieces off the board. This reportedly amused Napoleon, who then played a real game with the machine, completing nineteen moves before tipping over his king in surrender.[47] Alternate versions of the story include Napoleon being unhappy about losing, playing the machine at a later time, playing one match with a magnet on the board, or playing a match with a shawl around the head and body of the Turk in an attempt to obscure its vision.[48]

In 1811, Mälzel brought the Turk to Milan for a performance with Eugène de Beauharnais, Prince of Venice and Viceroy of Italy. Beauharnais enjoyed the machine so much that he offered to purchase it from Mälzel. After some protracted bargaining, Beauharnais acquired the Turk for 30,000 francs – three times what Mälzel had paid – and kept it for four years. In 1815, Mälzel returned to Beauharnais in Munich and asked to buy back the Turk. There are differing accounts of the conditions of the sale.[b][c]

"Leaving Bavaria with the Automaton, Maelzel was once more en route, as travelling showman of the wooden genius. Other automata were adopted into the family, and a handsome income was realised by their ingenious proprietor."[49] Mälzel brought the Turk back to Paris, where Boncourt is thought to have been its primary operator,[49] and where Mälzel made the acquaintance of many of the leading chess players at Café de la Régence. He stayed in France with the machine until 1818, when he moved to London and held a number of performances with the Turk and many of his other machines. In London, Mälzel and his act received a large amount of press, and he continued to improve the machine,[52] ultimately installing a voice box so that the machine could say "Échec!" when placing a player in check.[53]

In 1819, Mälzel took the Turk on a tour of the United Kingdom. There were several new developments in the act, such as allowing the opponent the first move and eliminating the king's bishop's pawn from the Turk's pieces. This pawn handicap created further interest in the Turk, and spawned a book by W. Hunneman chronicling the matches played with this handicap.[54][55] Despite the handicap, the Turk (operated by Mouret at the time)[56] ended up with forty-five victories, three losses and two stalemates.[57]

North American tour

[edit]The appearances of the Turk were profitable for Mälzel, and he continued by taking it and his other machines to the United States. In 1826, he opened an exhibition in New York that slowly grew in popularity, giving rise to many newspaper articles and anonymous threats of exposure of the fraud. Mälzel's problem was finding a talented operator for the machine,[58] having trained an unknown woman in France before touring the United States. He ended up recalling a former operator from Alsace, William Schlumberger, to work for him again once he was able to provide the money for Schlumberger's transport.[citation needed]

Upon Schlumberger's arrival, the Turk debuted in Boston. Mälzel claimed that "the players of Boston are at least equal to those of New York" and promised that in Boston the Turk would offer to play not only "end-games" but also full matches.[59] The Turk was a success in Boston for many weeks, and the tour moved to Philadelphia for three months,[citation needed] during which period it "lost a full game over the course of two exhibitions to a 'Mrs. Fisher', described in the front-page [Baltimore] Gazette headline as a 'Lady' of the city".[60] Following Philadelphia, the Turk moved to Baltimore, where it played for several months, losing a match against Charles Carroll, a signer of the Declaration of Independence. The exhibition in Baltimore brought news that two brothers had constructed their own machine, the Walker Chess-player. Mälzel viewed the competing machine and attempted to buy it, but the offer was declined and the duplicate machine toured for a number of years, never receiving the fame that Mälzel's machine did and eventually falling into obscurity.[61]

Mälzel continued with exhibitions around the United States until 1828, when he took some time off and visited Europe, returning in 1829. Throughout the 1830s, he continued to tour the United States, exhibiting the machine as far west as the Mississippi River and visiting Canada. In Richmond, Virginia, the Turk was observed by Edgar Allan Poe, who was writing for the Southern Literary Messenger. Poe's essay "Maelzel's Chess-Player" was published in April 1836 and is the most famous essay on the Turk, even though many of Poe's hypotheses were incorrect.[d][63]

Mälzel eventually took the Turk on his second tour to Havana, Cuba. In Cuba, Schlumberger died of yellow fever in February 1838, leaving Mälzel without an operator for his machine. Dejected, Mälzel died at sea in July 1838 at the age of 65 during his return trip, leaving his machinery with the ship captain.[64][65]

Later years

[edit]When the ship on which Mälzel died returned, his various machines, including the Turk, fell into the hands of a friend of Mälzel's, the businessman John Ohl. He attempted to auction off the Turk; but, owing to low bidding, ultimately bought it himself for $400 (equivalent to $12,000 in 2024).[66] Only when John Kearsley Mitchell from Philadelphia, Edgar Allan Poe's personal physician and an admirer of the Turk, approached Ohl did the Turk change hands again.[2] Mitchell formed a restoration club and started the repair of the Turk for public appearances, completing the restoration in 1840.[67]

As interest in the Turk grew, Mitchell and his club chose to donate it to the Philadelphia Museum (also known as the Chinese Museum) of Charles Willson Peale. While the Turk still occasionally gave performances, it was eventually relegated to the corners of the museum and forgotten about until 5 July 1854, when a fire that started at the National Theater in Philadelphia reached the Museum and destroyed the Turk.[68] Mitchell's son Silas Weir Mitchell believed he had heard "through the struggling flames . . . the last words of our departed friend, the sternly whispered, oft repeated syllables, échec! échec!!"[69]

Publication of the mechanism

[edit]According to James Cook, by the mid-1820s "hundreds, if not thousands, of 'approaches' had been made toward discovering the secret [of the mechanical Turk], many of which were actually very close to the answer".[70]

The illusion was exposed in 1827 during a match in Baltimore when the unusually high temperature rendered the operator, William Schlumberger, faint. He signalled to Mälzel to stop the game; but before Mälzel could act on this, Schlumberger, in desperation, escaped from the cabinet of the Turk. That he did so was not entirely clear to the audience; however two teens enjoying a free view of the performance from a nearby rooftop saw and understood what had happened. One told his father, who told the Baltimore Gazette, which published an article on its front page saying that "This ingenious contrivance . . . has at length been discovered by accident to be merely the case in which a human agent has always been concealed, when exhibited to an audience."[e]

Although Mälzel withdrew the Turk from his travelling show, which continued with "The Conflagration of Moscow" and "The Trumpeter", the Baltimore Gazette story had little impact, with George Allen (described as "Greek Professor in the University of Pennsylvania"[73]) writing:[74]

[N]obody credited the pretended discovery. The world had set its heart upon believing that the secret, which had puzzled mechanicians, mathematicians, and monarchs, for more than half a century, was something quite too deep to be penetrated by a couple of boys. The National Intelligencer, of Washington . . . sagaciously treated the Gazette article as having emanated from Maelzel himself – "the tale of a discovery was but a clever device of the proprietor to keep alive the interest of the community in his exhibition".

Lesser newspapers, suggests Allen, were too timid to contradict the Intelligencer and Mälzel's business was little impacted.[75]

Of the many books and articles written at the time about the mechanism of the Turk, most were inaccurate and drew incorrect inferences. The first articles were published in the French magazine Le Magasin pittoresque in 1834.[76] It was not until Silas Mitchell's article for The Chess Monthly in 1857 that the secret was fully revealed. Mitchell, son of the final private owner of the Turk,[77] wrote that "perhaps no secret was ever kept as the Turk's has been. Guessed at, in part, many times, no one of the several explanations in our possession has ever practically solved this amusing puzzle". As the Turk had been lost to fire, Mitchell felt that there were "no longer any reasons for concealing from the amateurs of chess, the solution of this ancient enigma".[78] Additionally, a biographical history about the Chess-player and Mälzel was presented in Daniel Willard Fiske's The Book of the First American Chess Congress (1859).[65] The account, "The Automaton Chess-Player in America", was written by George Allen, in the form of a letter to William Lewis, a former operator of the Turk.

In 1859, a letter published in the Philadelphia Sunday Dispatch by William F. Kummer,[79] who worked as an operator under John Mitchell, revealed another piece of the fraud: a candle inside the cabinet, necessary to provide light for the operator. A series of tubes led from the lamp to the turban of the Turk for ventilation. The smoke rising from the turban would be disguised by the smoke coming from the other candelabra in the area where the game was played.[80] Later that year an uncredited article[81] appeared in Littell's Living Age that purported to be the story of the Turk from French magician Jean Eugène Robert-Houdin. This was rife with errors ranging from dates of events to a story of a Polish officer whose legs had been amputated, but who was rescued by Kempelen and smuggled back to Russia inside the machine.[82]

A new article about the Turk did not turn up until 1899, when The American Chess Magazine published an account of the Turk's match with Napoleon.[83] The story was basically a review of previous accounts, and a substantive published account would not appear until 1947, when Chess Review published articles by Kenneth Harkness and Jack Straley Battell that amounted to a comprehensive history and description of the Turk, complete with new diagrams that synthesized information from previous publications.[84] Another article written in 1960 for American Heritage by Ernest Wittenberg[85] provided new diagrams describing how the operator sat inside the cabinet.[86]

In Henry A. Davidson's 1945 publication A Short History of Chess, significant weight is given to Poe's essay which erroneously suggested that the player sat inside the Turk figure, rather than on a moving seat inside the cabinet. A similar error would occur in Alex G. Bell's 1978 book The Machine Plays Chess, which falsely asserted that "the operator was a trained boy (or very small adult) who followed the directions of the chess player who was hidden elsewhere on stage or in the theater . . ."[87] More books were published about the Turk toward the end of the 20th century. Along with Bell's book, Charles Michael Carroll's The Great Chess Automaton (1975) focused more on the studies of the Turk. Bradley Ewart's Chess: Man vs. Machine (1980)[88] discussed the Turk as well as other purported chess-playing automata.[89] It was not until the creation of Deep Blue, IBM's 1997 attempt at a computer that could challenge the world's best players,[90] that interest increased again, and two more books were published: Gerald M. Levitt's The Turk, Chess Automaton (2000),[f] and Tom Standage's The Turk: The Life and Times of the Famous Eighteenth-Century Chess-Playing Machine (2002).[g]

Legacy

[edit]

Owing to the Turk's popularity and mystery, its construction inspired a number of inventions and imitations,[2] including Ajeeb, or "The Egyptian", an American imitation built by Charles Hopper that President Grover Cleveland played in 1885,[91] and Mephisto, advertised as the "most famous" machine, of which little is known.[92] The first imitation was made while Mälzel was in Baltimore. Created by the Brothers Walker, the "American Chess Player" made its debut in May 1827 in New York.[93] El Ajedrecista was built in 1912 by Leonardo Torres Quevedo as a chess-playing automaton and made its public debut during the Paris World Fair of 1914. Capable of playing rook and king versus king endgames using electromagnets, it was the first true chess-playing automaton and a precursor of sorts to Deep Blue.[91]

The Turk was visited in London by Rev. Edmund Cartwright in 1784. He was so intrigued by the Turk that he questioned whether it would be more difficult to construct a power loom than a device that would play chess.[h] Cartwright would patent the prototype for a power loom within the year.[95] Sir Charles Wheatstone, an inventor, saw a later appearance of the Turk while it was owned by Mälzel. He also saw some of Mälzel's speaking machines, and Mälzel later demonstrated the speaking machines to Wheatstone and his teenage son. Alexander Graham Bell obtained a copy of a book by Wolfgang von Kempelen on speaking machines after being inspired by seeing a similar machine built by Wheatstone; Bell went on to file the first successful patent for the telephone.[2]

The Turk has inspired works of literary fiction. The narrator of Jean Paul's story Menschen sind Maschinen der Engel (written in 1785)[96] starts off by saying that we humans are merely the furniture of the true inhabitants of the world, angels; and it is "obvious [that] our industriousness, which works against our happiness, is conducive to other beings' happiness, whose hands conduct ours as their tools". Chess-playing machines exemplify the building by machines (that is, people) of machines; of which the narrator's description culminates in a "deliberate confusion of chess-playing humans and chess-playing machines", "[leaving] the reader incessantly bewildered about the status of the story's actors (as well as the reader's own status) as machine or as human."[97] Ambrose Bierce's 1899 short story "Moxon's Master"[98] is a morbid tale about a chess-playing automaton that resembles the Turk, as described by Poe.[99] In 1938, John Dickson Carr published The Crooked Hinge,[100] among whose puzzles is an automaton that operates in a way that is unexplainable to the characters.[101] Gene Wolfe's 1977 science fiction short story "The Marvelous Brass Chessplaying Automaton"[102] also features a device very similar to the Turk.[103] Robert Löhr's 2007 novel The Chess Machine (published in the UK as The Secrets of the Chess Machine)[104] focuses on the man inside the machine, a dwarf named Tibor.[105][106] F. Gwynplaine MacIntyre's 2007 story "The Clockwork Horror"[107] reconstructs Poe's encounter with Mälzel's chess-player, and also establishes (from contemporary advertisements in a Richmond newspaper) precisely when and where this took place.[citation needed]

In the first of his Theses on the Philosophy of History (Über den Begriff der Geschichte, 1940), Walter Benjamin wrote of the Mechanical Turk that "one can imagine a philosophical counterpart to this device. The puppet called "historical materialism" is to win all the time. It can easily be a match for anyone if it enlists the services of theology, which today, as we know, is wizened and has to keep out of sight."[108]

In Raymond Bernard's silent feature film The Chess Player (Le Joueur d'échecs, 1927), a young Polish nationalist on the run from the occupying Russians is hidden inside a chess-playing automaton closely based on Kempelen's Turk.[109][110]

There have been at least two television films based on the Turk. A 13-episode French-Italian-Austrian-Hungarian series, Les Évasions célèbres (Famous Escapes) was broadcast on ORTF in 1972 as well as elsewhere (e.g. East Germany in 1977). One 55-minute episode, Le Joueur d'échecs (Der Schachspieler), directed by Christian-Jaque, has Napoleon (Robert Manuel) encounter the Automaton in Von Kempelen's castle, play, and lose.[111] El jugador de ajedrez or Le Joueur d'échecs de Maelzel, a 54-minute television film produced in Mexico and France, and directed by Juan Luis Buñuel, was first broadcast in 1981 as one of a series of films based on Poe.[112][113]

Reconstruction

[edit]

John Gaughan, an American manufacturer of equipment for magicians based in Los Angeles, spent $120,000 (equivalent to $360,000 in 2024) building his own version of Kempelen's machine from 1984 to 1989.[114] The machine uses the original chessboard, which had been stored separately and was not destroyed in the fire. The first public display of Gaughan's Turk was in November 1989 at the Los Angeles Conference on Magic History. The machine was presented much as Kempelen presented the original, except that the opponent was replaced by a computer running a chess program.[115]

Notes

[edit]- ^ As Mitchell only specifies these dimensions to the nearest half-foot, metric versions can only be precise to the nearest multiple of 15 centimetres; thus very roughly 105 cm × 60 cm × 75 cm.

- ^ "[T]he sagacious Mr. Maelzel, who had already experienced some regret at parting with his protégé, requested the favour to be again reinstated in the charge, promising to pay Eugene the interest of the thirty thousand francs Mr. M. had pocketed. This proposition was graciously conceded by the gallant Beauharnois, and Maelzel thus had the satisfaction of finding he had made a tolerably good bargain, getting literally the money for nothing at all!"[49]

- ^ "The writer in the Palamède makes the result a kind of partnership in an exhibition-tour – the title of the Automaton was to remain in the princely owner, and Maelzel was to pay the interest of the original cost as his partner's fair proportion of the profits. But another account – current, I believe, at Munich – makes the transaction to have been a sale: Maelzel bought back the Automaton for the same thirty thousand francs, and was to pay for it out of the profits of his exhibitions – 'Provided, nevertheless', that Maelzel was not to leave the Continent to give such exhibitions. The latter account I believe to be the more correct one."[50]

- ^ One was that a chess-playing machine must always win: "The Automaton does not invariably win the game. Were the machine a pure machine this would not be the case – it would always win. The principle being discovered by which a machine can be made to play a game of chess, an extension of the same principle would enable it to win a game; a farther extension would enable it to win all games – that is, to beat any possible game of an antagonist. A little consideration will convince any one that the difficulty of making a machine beat all games, is not in the least degree greater, as regards the principle of the operations necessary, than that of making it beat a single game."[62]

- ^ "The Chess-player Discovered". Baltimore Gazette. 1 June 1827.[71][72]

- ^ "The Turk, Chess Automaton". Product listing. McFarland Publishers. Archived from the original on 15 October 2006. Retrieved 1 January 2007.

- ^ "The Turk: The Life and Times of the Famous Eighteenth-Century Chess-Playing Machine". Product listing. Walker Books. Archived from the original on 31 December 2006. Retrieved 1 January 2007.

- ^ ". . . I controverted, however, the impracticability of [a weaving mill], by remarking that there had been lately exhibited in London an automaton figure which played at chess. 'Now you will not assert, gentlemen', said I, 'that it is more difficult to construct a machine that shall weave, than one which shall make all the variety of moves which are required in that complicated game'."[94]

References

[edit]- ^ a b Standage 2002, p. 88.

- ^ a b c d e f g Jay, Ricky (2000). "The Automaton Chess Player, the Invisible Girl, and the Telephone". Jay's Journal of Anomalies. Vol. 4, no. 4.

- ^ Windisch (1784), p. 18.

- ^ Poe 1836.

- ^ Windisch (1784).

- ^ Rice 2004, p. 12.

- ^ Standage 2002, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Mitchell 1857, p. 41.

- ^ a b Standage 2002, p. 24.

- ^ Standage 2002, pp. 24–27.

- ^ Standage 2002, pp. 195–199.

- ^ Standage 2002, p. 202.

- ^ Walker 1839.

- ^ Hankins & Silverman 1995, p. 191.

- ^ Levitt 2000, p. 40.

- ^ Windisch (1784), p. 15.

- ^ Levitt 2000, pp. 147–150.

- ^ Standage 2002, pp. 27–29.

- ^ Atkinson 1998, pp. 15–16.

- ^ Poe 1836, p. 321.

- ^ Standage 2002, pp. 203–204.

- ^ Levitt 2000, p. 17.

- ^ Louis Dutens, from a letter (À Presbourg, ce 24 juillet 1770) published in Mercure de France, circa October 1770; translated into English and reprinted in The Gentleman's Magazine (24 January 1771, pp. 26–27); translation taken from Levitt 2000.

- ^ Standage 2002, p. 30.

- ^ a b Standage 2002, pp. 30–31.

- ^ Standage 2002, pp. 204–205.

- ^ Hindenburg 1784.

- ^ Levitt 2000, pp. 33–34.

- ^ Windisch (1784), p. 43.

- ^ Standage 2002, pp. 36–38.

- ^ Hamilton 2013.

- ^ Standage 2002, pp. 40–42.

- ^ Standage 2002, pp. 44–45.

- ^ Standage 2002, p. 49.

- ^ Hooper & Whyld 1996, pp. 431–433.

- ^ Levitt 2000, p. 26.

- ^ Levitt 2000, pp. 27–29.

- ^ Levitt 2000, pp. 30–31.

- ^ Thicknesse 1794.

- ^ Racknitz 1789.

- ^ Levitt 2000, pp. 33–38.

- ^ Standage 2002, pp. 90–91.

- ^ Levitt 2000, pp. 37–38.

- ^ Levitt 2000, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Levitt 2000, p. 30.

- ^ Standage 2002, pp. 105–106.

- ^ Ewart 1980, pp. 49–53.

- ^ Levitt 2000, pp. 39–42.

- ^ a b c Walker 1839, p. 726.

- ^ Allen 1859, p. 426.

- ^ Levitt 2000, p. 45.

- ^ Levitt 2000, pp. 45–48.

- ^ Standage 2002, p. 125.

- ^ Levitt 2000.

- ^ Hunneman 1820.

- ^ Hooper & Whyld 1996, p. 265.

- ^ Levitt 2000, p. 49.

- ^ Levitt 2000, pp. 68–69.

- ^ Cook 1995, p. 249.

- ^ Cook 1995, p. 250.

- ^ Levitt 2000, pp. 71–8.

- ^ Poe 1836, p. 323.

- ^ Levitt 2000, pp. 83–86.

- ^ Levitt 2000, pp. 87–91.

- ^ a b Allen 1859.

- ^ Levitt 2000, pp. 92–93.

- ^ Levitt 2000, pp. 94–95.

- ^ Levitt 2000, pp. 97.

- ^ Mitchell 1857, p. 4.

- ^ Cook 1995, p. 252.

- ^ Allen 1859, pp. 451–452.

- ^ Cook 1995, p. 253, n. 56.

- ^ Fiske 1859, p. viii.

- ^ Allen 1859, p. 452.

- ^ Allen 1859, pp. 452–453.

- ^ Saunders et al. 2010, p. 101.

- ^ Levitt 2000, p. 236.

- ^ Mitchell 1857, p. 5.

- ^ Kummer, William F. (February 1859). "Maelzel's automaton chess-player". Philadelphia Sunday Dispatch.

- ^ Levitt 2000, p. 150.

- ^ "The automaton chess-player". Littell's Living Age. 3rd. No. 62. 4 June 1859. pp. 585–592.

- ^ Levitt 2000, p. 151.

- ^ "Napoleon and the automaton". American Chess Magazine. Vol. 3. p. 164.

- ^ Harkness, Kenneth; Battell, Jack Straley (February–November 1947). "This made chess history". Chess Review.

- ^ Wittenberg 1960.

- ^ Levitt 2000, pp. 151–152.

- ^ Levitt 2000, p. 153.

- ^ Ewart 1980.

- ^ Levitt 2000, pp. 154–155.

- ^ Hsu 2002.

- ^ a b Jiménez, Ramón. "The Rook Endgame Machine of Torres y Quevedo". ChessBase, 20 July 2004. Accessed 26 August 2025

- ^ Levitt 2000, p. 154.

- ^ Allen 1859, p. 456.

- ^ Ashenhurst 1879, pp. 46–47.

- ^ Levitt 2000, pp. 31–32.

- ^ Jean Paul 1927.

- ^ Voskuh 2007, pp. 299–303.

- ^ Bierce, Ambrose (16 April 1899). "A Night at Moxon's". The Examiner. Vol. LXVIII, no. 106. San Francisco. p. 22 – via Newspapers.com. Reprinted in "Moxon's Master". Can Such Things Be?. The Collected Works of Ambrose Bierce. Vol. III. New York: Neale. 1910. pp. 88–105.

- ^ Miller 1932, pp. 140–141.

- ^ "Mystery of the Month". Time, 31 October 1938. Accessed 14 February 2007.

- ^ Joshi 1990.

- ^ Wolfe, Gene (1977). "The Marvelous Brass Chessplaying Automaton". In Carr, Terry (ed.). Universe 7. Garden City, NY: Doubleday. pp. 113–133 – via Internet Archive. Reprinted: Saberhagen, Fred; Saberhagen, Joan, eds. (1982). "The Marvelous Brass Chessplaying Automaton". Pawn to Infinity. New York: Ace Books. pp. 3–25. ISBN 0-441-65482-7 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Langford 2005, p. 113.

- ^ Löhr, Robert (2007). The Chess Machine. Translated by Bell, Anthea. New York: Penguin Press. ISBN 978-1-59420-126-4 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Charles 2007.

- ^ Anderson 2007.

- ^ James Robert Smith & Stephen Mark Rainey (editors), Evermore, Arkham House, 2007; reprinted in Stephen Jones (editor), The Mammoth Book of Best New Horror, Carroll & Graf, 2007.

- ^ Benjamin 1968, p. 253.

- ^ Valin 1987, pp. 52–53.

- ^ Furniss 2004.

- ^ "Schachspieler, Der (TV-Film) (1972)". Fernsehen der DDR – Online Lexikon der DDR-Fernsehfilme, Fernsehspiele und TV-Inszenierungen (in German). Retrieved 27 August 2025.

- ^ "Histoires extraordinaires: Le Joueur d'échecs de Maelzel" [Extraordinary Tales: Maelzel's Chess-Player]. BDFF: Base de données de films français (in French). Retrieved 27 August 2025.

- ^ Garmendia, Arturo (3 July 2018). "La dinastía Buñuel. Un despedida a Juan Luis" [The Buñuel dynasty: A farewell to Juan Luis]. Corre Camara (in Spanish). Retrieved 27 August 2025.

- ^ Levitt 2000, p. 243.

- ^ Standage 2002, pp. 216–217.

Sources

[edit]- Allen, George (1859). "The history of the automaton chess-player in America. A letter addressed to William Lewis Esq., London". The Book of the First American Chess Congress: Containing the Proceedings of that Celebrated Assemblage, held in New York, in the Year 1857. By Fiske, Daniel Willard. New York: Rudd & Carleton. pp. 420–484 – via Internet Archive. (Signed by G.A., who Fiske identifies as George Allen in the preface to the book.)

- Anderson, Hephzibah (3 June 2007). "Confucius say: Do snap out of it". The Observer.

- Ashenhurst, Thos. R. (1879). A Practical Treatise on Weaving and Designing of Textile Fabrics: With Chapters on the Principles of Construction of the Loom, Calculations and Colour (PDF). Bradford: T. Brear – via Internet Archive.

- Atkinson, George (1998). Chess and Machine Intuition. Exeter: Intellect. ISBN 978-0-5852-4481-5.

- Benjamin, Walter (1968). Illuminations. New York: Schocken. ISBN 978-0-8052-0241-0.

- Charles, Ron (30 June 2007). "Checkmate". Washington Post.

- Cook, James W. (Winter 1995). "From the Age of Reason to the Age of Barnum: The Great Automaton Chess-Player and the Emergence of Victorian Cultural Illusionism". Winterthur Portfolio. 30 (4). University of Chicago Press: 231–257. JSTOR 4618515.

- Ewart, Bradley (1980). Chess, Man vs. Machine. London: A. S. Barnes. ISBN 978-0-498-02167-1 – via Internet Archive.

- Fiske, Daniel Willard (1859). The Book of the First American Chess Congress: Containing the Proceedings of that Celebrated Assemblage, held in New York, in the Year 1857. New York: Rudd & Carleton – via Internet Archive.

- Furniss, Maureen (Spring 2004). "Le Joueur d'echecs/The Chess Player (review)". The Moving Image. 4 (1). University of Minnesota Press: 149–151. doi:10.1353/mov.2004.0007.

- Hamilton, Sheryl (2013). Invented Humans: Kinship and Property in Persons. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-1-4426-6964-2.

- Hankins, Thomas L.; Silverman, Robert J. (1995). Instruments and the Imagination. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-02997-9.

- Hindenburg, Carl Friedrich (1784). Ueber den Schachspieler des Herrn von Kempelen: Nebst einer Abbildung und Beschreibung seiner Sprachmaschine [On Mr. von Kempelen's chess player: With an illustration and description of his language machine] (in German). Leipzig: Johann Gottfried Müllerschen Buchhandlung – via Münchener DigitalisierungsZentrum Digitale Bibliothek.

- Hooper, David; Whyld, Kenneth (1996) [1992]. The Oxford Companion to Chess (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280049-7.

- Hsu, Feng-hsiung (2002). Behind Deep Blue: Building the Computer that Defeated the World Chess Champion. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-09065-8.

- Hunneman, W. (1820). Chess. A Selection of Fifty Games, from Those Played by the Automaton Chess-Player, During Its Exhibition in London, in 1820, Taken Down, by Permission of Mr. Maelzel, at the Time They Were Played. London: The Exhibition Room, and A. Maxwell. OCLC 559305144 – via Hathitrust. (Credited to "W.H.", widely identified as W. Hunneman.)

- Jean Paul (1927). "Menschen sind Maschinen der Engel" [Humans are machines of the angels]. In Berend, Eduard (ed.). Jean Pauls Sämtliche Werke: historisch-kritische Ausgabe, Part 2 (in German). Vol. 1. Weimar: Hermann Böhlaus Nachfolger. pp. 1028–30. OCLC 945170335.

- Joshi, S. T. (1990). John Dickson Carr: A Critical Study. Bowling Green, Ohio: Bowling Green State University Popular Press. ISBN 978-0-87972-477-1.

- Langford, David (2005). "Chess". In Westfahl, Gary (ed.). The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Science Fiction and Fantasy: Themes, Works, and Wonders. Vol. 1: Themes A–K. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. pp. 112–114. ISBN 0-313-32951-6.

- Levitt, Gerald M. (2000). The Turk, Chess Automaton. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-0778-1.

- Miller, Arthur M. (May 1932). "The influence of Edgar Allan Poe on Ambrose Bierce". American Literature. 4 (2): 130–150. JSTOR 2920282.

- Mitchell, S[ilas] W[eir] (January–February 1857). "The Last of a Veteran Chess Player". The Chess Monthly. Vol. 1. pp. 3–7, 40–45. hdl:2027/hvd.hn43vw; reprinted as: "Appendix L: Mitchell's 'The Last of a Veteran Chess Player' (1857)" in Levitt 2000, pp. 236–240.

- Poe, Edgar Allan (1836). "Maelzel's Chess-Player". Southern Literary Messenger. Vol. 2, no. 5. pp. 318–326 – via University of Michigan Library Digital Collections. (Additionally available via the Edgar Allan Poe Society of Baltimore, Maryland.)

- Racknitz, Joseph Friedrich Freyherr zu (1789). Ueber den Schachspieler des Herrn von Kempelen und dessen Nachbildung [On Mr. von Kempelen's chess player and its replica] (in German). Leipzig: Joh. Gottl. Immanuel Breitkopf. OCLC 457435484 – via Google Books.

- Rice, Stephen Patrick (2004). Minding the Machine: Languages of Class in Early Industrial America. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-22781-1.

- Saunders, Rob; Gemeinboeck, Petra; Lombard, Adrian; Bourke, Dan; Kocabali, Baki (2010). "Curious Whispers: An Embodied Artificial Creative System". Proceedings of the International Conference on Computational Creativity, Lisbon, Portugal, January 2010. Coimbra: Department of Informatics Engineering, University of Coimbra. pp. 100–109. ISBN 978-989-96-0012-6.

- Standage, Tom (2002). The Turk: The Life and Times of the Famous 19th Century Chess-Playing Machine. New York: Walker. ISBN 978-0-8027-1391-9.

- Thicknesse, Philip (1794). The Speaking Figure and the Automaton Chess Player, Exposed and Detected. London: John Stockdale. OCLC 83389608 – via Google Books. (Author not specified, but widely believed to be Thicknesse.)

- Valin, Pierre (Autumn 1987). "Le Double Jeu de l'automate". Quaderni (in French) (2): 45–55. doi:10.3406/quad.1987.1860.

- Voskuh, Adelheid (2007). "Motions and passions: Music-playing women automata and the culture of affect in late eighteenth-century Germany". In Riskin, Jessica (ed.). Genesis Redux: Essays in the History and Philosophy of Artificial Life. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 293–320. ISBN 978-0-226-72080-7. (Also ISBN 978-0-226-72081-4.)

- Walker, George (June 1839). "Anatomy of the Chess Automaton". Fraser's Magazine for Town and Country. Vol. 19, no. 114. James Fraser. pp. 717–731 – via Internet Archive. (Credited to "G.W.", elsewhere identified as George Walker.(Cook 1995, p. 246, n. 36))

- Windisch, Karl Gottlieb von (1784). Inanimate Reason; or A Circumstantial Account of That Astonishing Piece of Mechanism, M. de Kempelen's Chess-Player . . . Translated from the original letters of M. Charles Gottlieb de Windisch. London: S. Bladon. OCLC 83370817 – via Google Books.

- Wittenberg, Ernest (February 1960). "Échec!". American Heritage. Vol. 11, no. 2. Archived from the original on 22 December 2007. (With a number of what appear to be OCR errors; without the diagrams.)

Further reading

[edit]- [Willis, Robert] (1821). An Attempt to Analyse the Automaton Chess Player of Mr. de Kempelen. London: J. Booth – via Internet Archive.

- Wood, Gaby (2002). Living Dolls: A Magical History of the Quest for Mechanical Life. London: Faber & Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-17879-7. (U.S. edition: Edison's Eve: A Magical History of the Quest for Mechanical Life. New York: Knopf, 2002. ISBN 9780679451129.) A history of robotics (hoaxes included).

External links

[edit]- Mechanical Turk player profile and games at Chessgames.com

- Dunning, Brian (21 July 2015). "Skeptoid #476: The Chess-Playing Mechanical Turk". Skeptoid.

- Randi, James. "The fabulous automaton chess-player". Part 1. "How it looked and what it did". Part 2. "How it worked and what happened to it". James Randi Educational Foundation. January–February 2000.